What we love about great sportsmen and women is the awe they induce on just a single platform. That they are in every other respect unremarkable, like us, but when put on a field of grass, a rubber 1,500m track, or inside four parallel rows of ropes, they seem to display almost outer-human levels of skill, akin to a superhero. It's why no-one grows out of sport.

When they step into real life, we see them bumble and struggle. Our heroes turn into aftershave-selling, ghostwritten-memoir-toting, ventriloquist dummies. That or their eccentric personalities that were once tamed and monitored during their careers run them deep into a ground of legal troubles and tragedy.

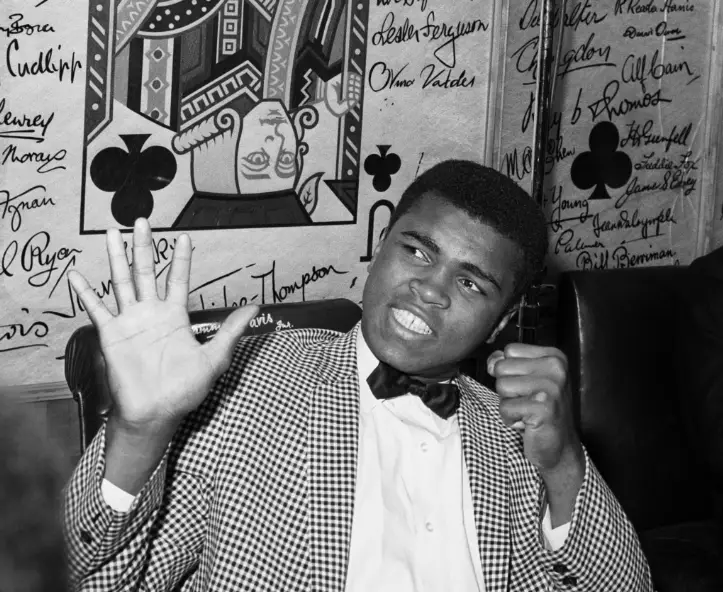

Ali in 1954. Image: PA

Advert

Every few decades, though, we get a sports personality that is actually just that - unlike the alarmingly-uniform Andy Murray - who manages to totally transcend their expired career. Someone that gains the attention and respect of people who would rather leap from a skyscraper than be forced to sit and watch two minutes of a baseball game. Muhammad Ali, who would have turned 75 today, was one of those people.

A product of Jim Crow America, Ali, born Cassius Clay, never fell prey to the sweetening invitations of phonies, opportunists, or even old age, staying as true as you like to himself right until his dying day on June 3 last year. He would never accept changing laws as moral absolutes, lending his voice to the civil rights movement well into the modern days of Trayvon Martin and Black Lives Matter, after Parkinson's Disease had long muted him. One instance from his childhood saw him visiting a five-and-ten-cents store for a drink of water only to be refused because of the colour of his skin. The pent up anger of being brought up in this segregated and discriminating world would eventually be his making.

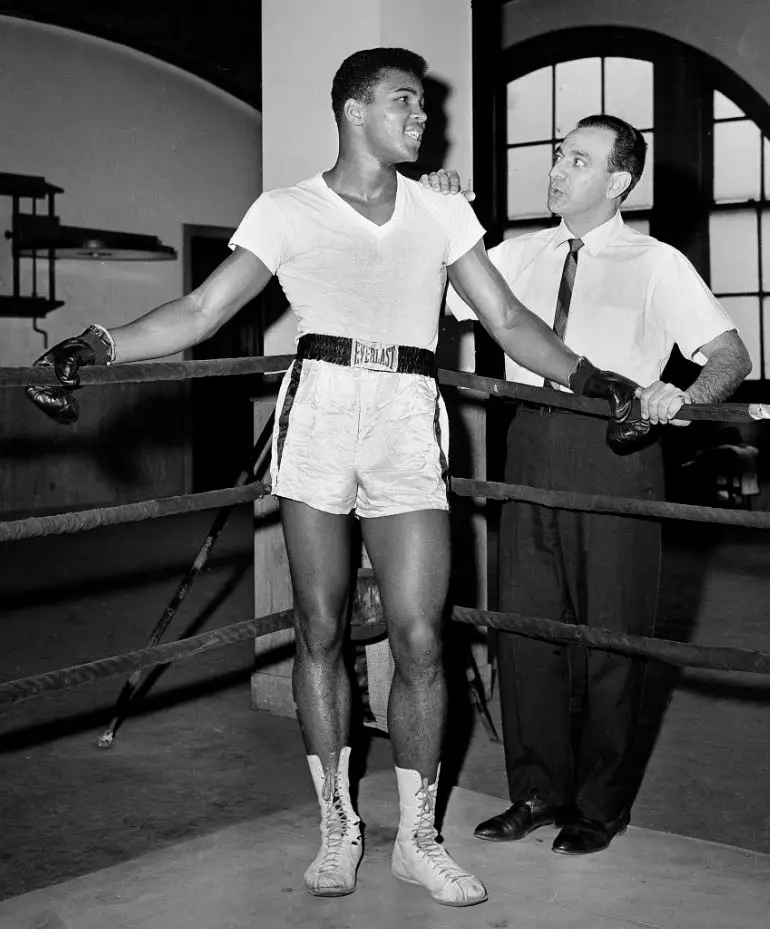

Ali training in 1962. Image: PA

Advert

Enraged and on the hunt for a man who'd stolen his bike one afternoon, he approached a policeman called Joe Martin to register the crime. Martin, a gym owner who liked giving a sense of purpose to kids off the street, advised the 12-year-old Clay to take up boxing.

"The sights and the sounds and the smell of the boxing gym excited me so much that I almost forgot about the bike," Ali remembered in a mid-1970s autobiography. "There were about 10 boxers, some hitting the speed bag, some in the ring sparring, some jumping rope. I stood there, smelling the sweat and the rubbing alcohol, and a feeling of awe came over me."

Ali after defeating Sonny Liston in 1964. Image: PA

Advert

Clay tore through the amateur ranks and ended up representing the U.S. at the 1960 Rome Olympics, bagging a gold medal, just 18-years-old. Ali and Martin's relationship would disintegrate after a visit to the Clay household where a contract was offered to the young light-heavyweight champion paying only $75 a week for 10 years. The story goes that Cassius Snr, Clay's father, shouted back: "The slave trade is over!"

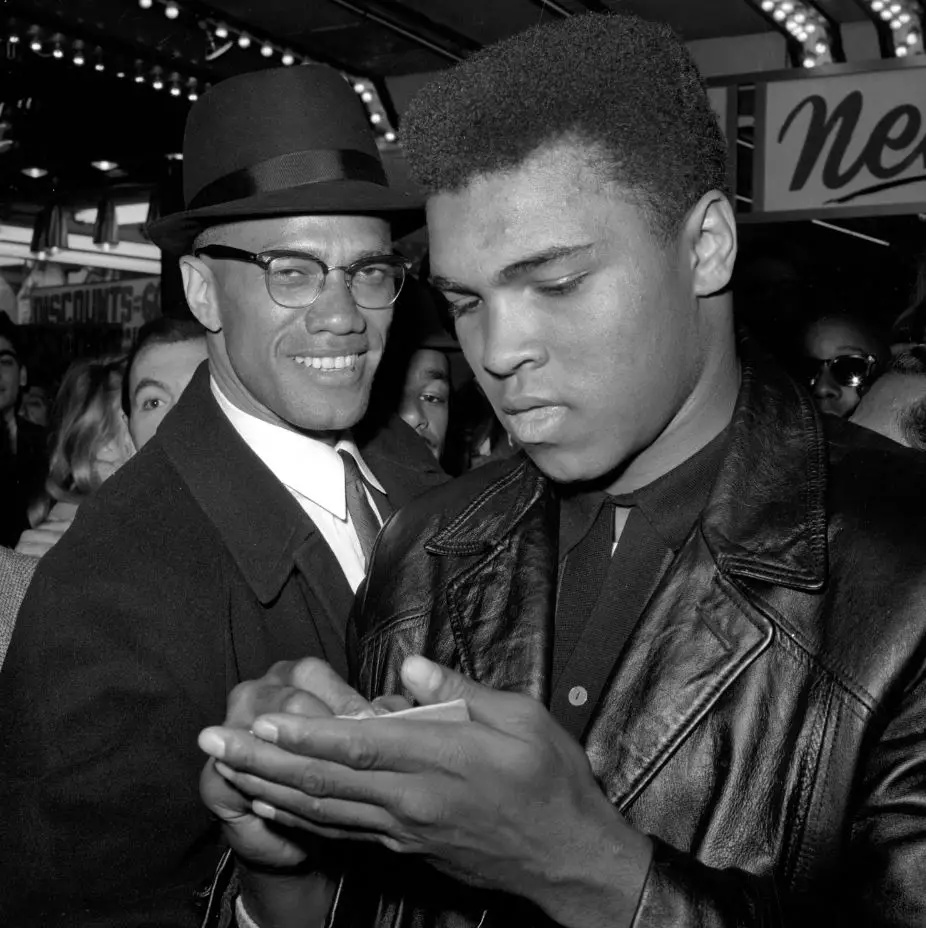

Instead, the young maverick went under the wing of the Louisville Sponsoring Group, going on to defeat Charles 'Sonny' Liston aged 22 on February 25, 1964 - one of the biggest feats in the sport's history - making him heavyweight champion of the world. And then two days later, Clay would make known not just his professional side to the world but his private, by embracing the controversial, black-supremacist religion Nation of Islam. The following month, he became "Muhammad Ali" and the rest, to borrow that stale stock phrase, is history.

Ali with Malcolm X. Image: PA

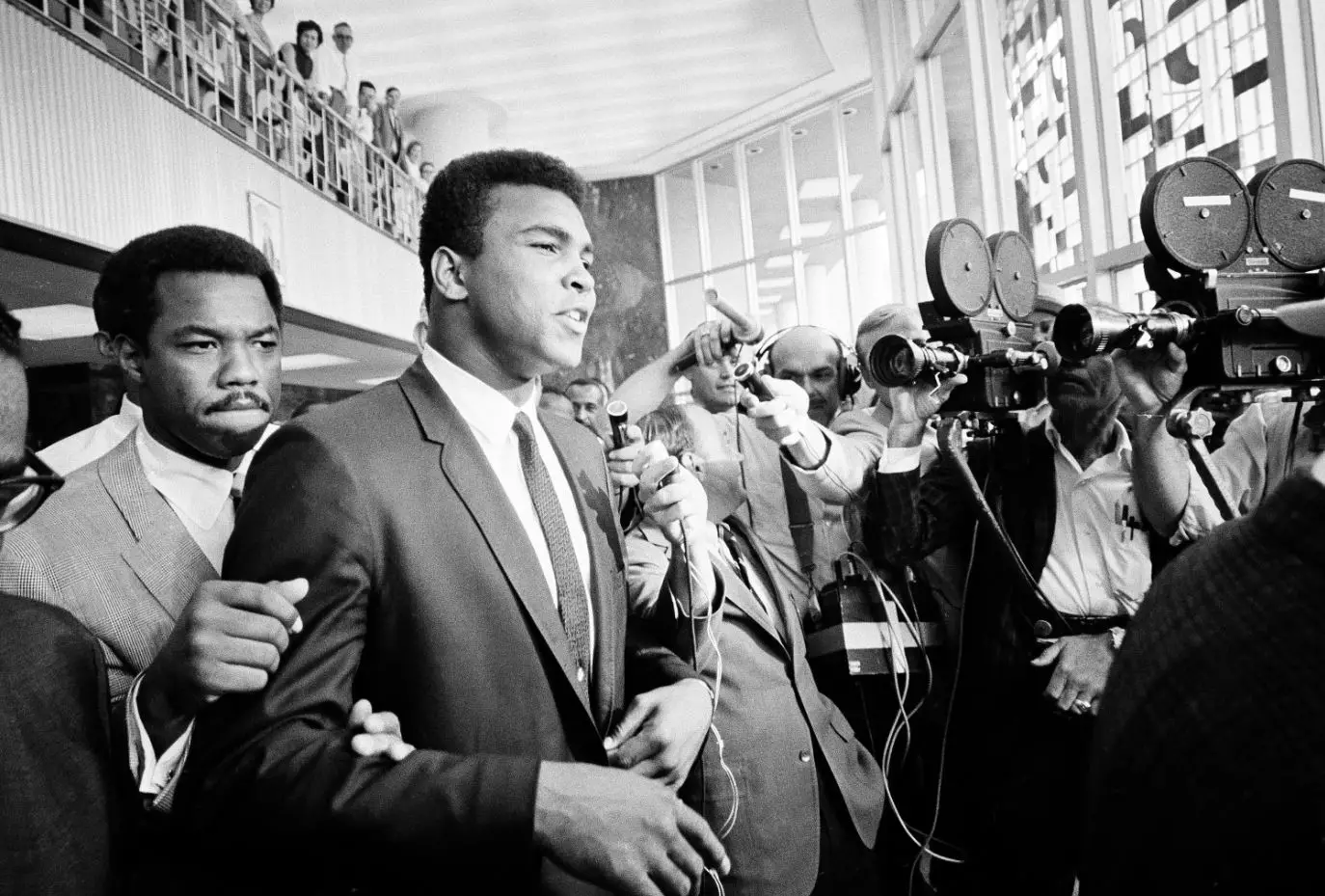

Ali addressing reporters outside court in 1967. Image: PA

Advert

The subsequent turbulence engulfing the counter-culture '60s movement did not serve well for Ali, who was making headlines with his contradictive rhetoric, one day insisting to a Soviet reporter that the United States was superior, the next, criticising his country for years of black emancipation. In 1967 he cited religious beliefs as a reason for not joining the U.S. Army in their fight against the Viet-Cong in Vietnam and he was sentenced to five years' imprisonment on June 20 that year. "My enemy is the white people," he said at the time. "Not Viet Cong or Chinese or Japanese. You my opposer when I want freedom. You my opposer when I want justice. You my opposer when I want equality. You won't even stand up for me in America for my religious beliefs - and you want me to go somewhere and fight, but you won't even stand up for me here at home?"

The conviction was overturned four years later by the US Supreme Court, but Ali still suffered the scorn of the boxing establishment and was both stripped of his title and banned from fighting for three-and-a-half years. When he came back into the new decade, the out-of-ring performances seemed to fare as well, if not sometimes better, than the in ring. His trio of appearances on Parkinson in the early-to-mid-1970s, in and around The Fight of the Century, Super Fight II, the Rumble in the Jungle and the Thrilla in Manilla, are now counted among TV's greatest talk show interviews. They show a comical, uber-witted and sometimes unsavoury Ali, who was still involved with the Nation of Islam before leaving in 1975 for a less separatist version of the religion, in an age before media training and soundbites.

Ali fighting Joe Frazier in 1971. Image: PA

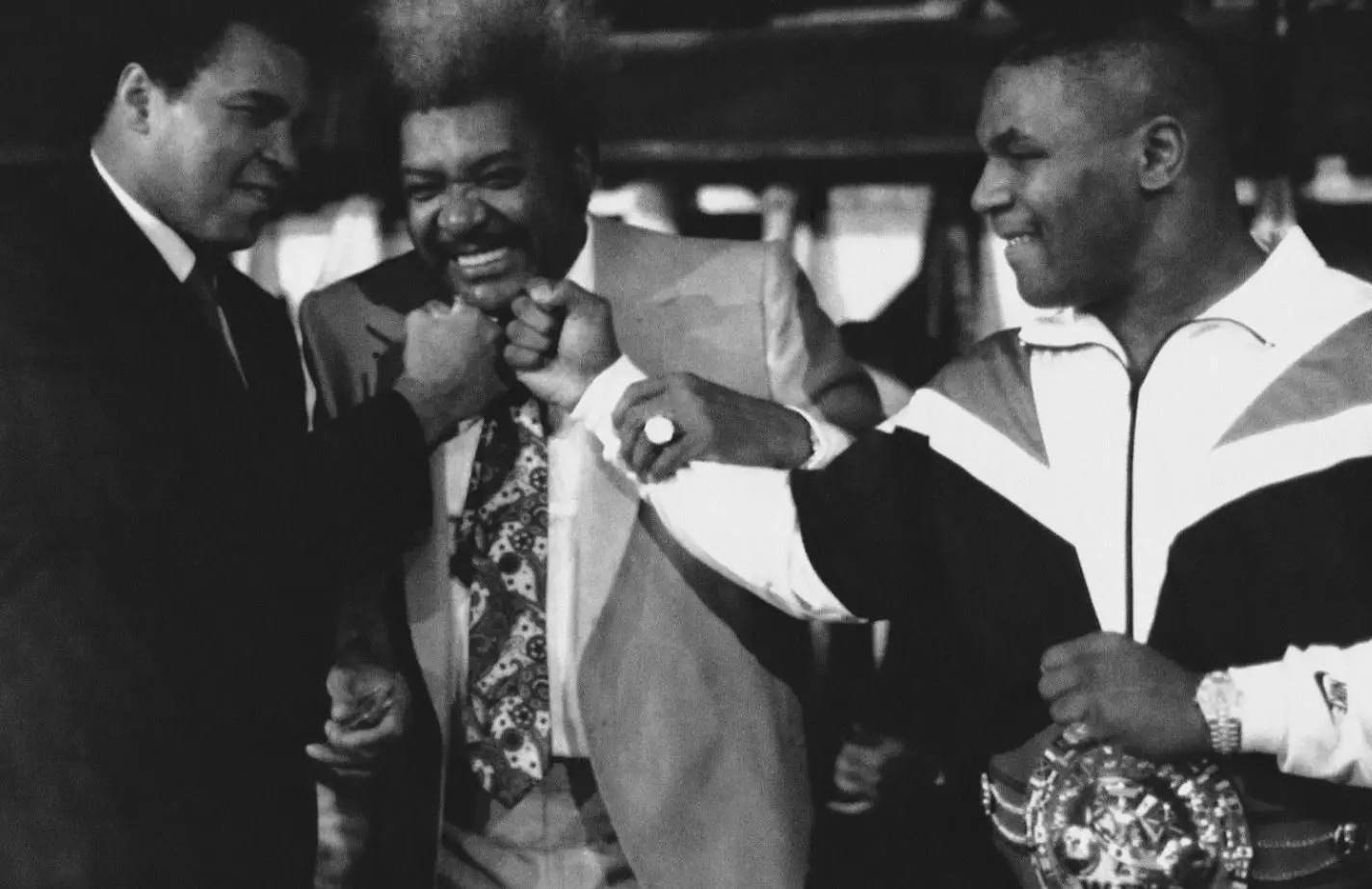

Ali with Don King and Mike Tyson, 1988. Image: PA

Advert

His final appearance in 1981 shows a more reclined, physically-spent Ali, who like many others in his game, had overstayed his welcome in the ring, leading to tragic circumstances. Unbeknownst to him until a 1984 diagnosis, the jaded boxer was experiencing the early symptoms of Parkinson's Disease, a disorder affecting motoring skills. "It was a slowness of movement that was his limiting factor at that time," Dr. Stanley Fahn, the neurologist who diagnosed Ali, recalled to CBS last year. "I saw immediately he had a masked face, that is, decreased expression. He had decreased blinking, and he had a typical Parkinson's tremor.

"You have slowness of movement, slows his reaction time, and that probably led to him being beaten up too much in the ring - and that probably worsened the trauma to his brain," he added.

Ali in Vietnam, 1994. Image: PA

Lighting the Olympic cauldron, 1996. Image: PA

Ali in 2014. Image: PA

At the time, Ali was told he would likely have 10 years max to live. He managed 32. Although gradually stunted and quietened over the course of the last three decades of his life, he continued to appear publicly, embracing his biggest and longest fight with dignity, achieving a silent sainthood figure respected across the globe as he did so. He refereed at Wrestlemania I, pep-talked Mike Tyson prior to his 1986 victory against Trevor Berbick, appeared at both the 1996 Atlanta and 2012 London Olympic games, lighting the cauldron with a now visibly trembling hand at the former.

During a 21-year career, Ali won 56 fights and lost five. He was and remains the idol for hundreds of boxers all over the world. We should remember him for that, obviously, but not go along with eulogising the dead merely in their prime, because to remember Ali in his illness is just as laudable if not more so.

Featured image credit: PA

Featured Image Credit:Topics: muhammad ali